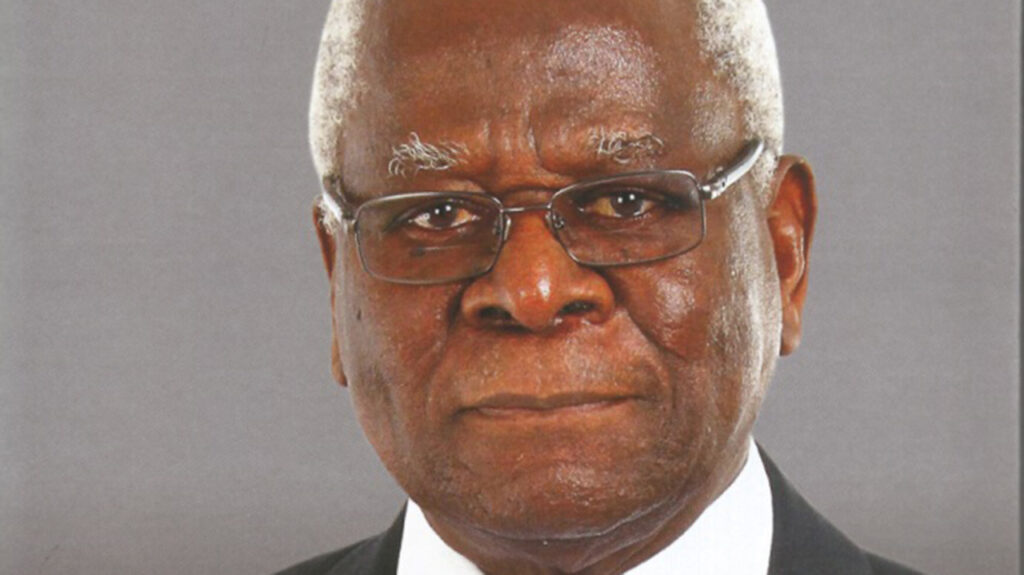

Ayodeji Ladipo Banjo, Emeritus Professor of English Language who passed on recently belongs in Nigeria’s Hall of Fame. A gifted teacher and excellent administrator, Banjo raised thousands of eminent persons for Nigeria.

Emeritus professor of virology, former President of Nigerian Academy of Science and chair of West Africa National Academy of Scientists, Oyewale Tomori, once told this anecdote about Banjo.

Shortly after graduation from University of California, Los Angeles, Banjo was posted to Government College, Ughelli as English teacher, replacing an expatriate.

Tomori and other students were nonplussed with the stringent attitude of their new teacher who was also stingy with marks. It was hard for them to comprehend why it was difficult to impress this young Nigerian; their former teacher, a mother tongue English language speaker, was more generous with marks.

But Banjo with his brilliant mind, a fierce sense of humor, and a kind heart was unflustered. With time, he proved to be the better teacher despite the fact that English was a second language.

Banjo belongs in the Hall of Fame because he helped, for almost two decades, to shape Nigeria’s literary culture as both scholar and chair of the Nigeria Prize for Literature, sponsored by Nigeria LNG Limited.

Because he felt a personal responsibility to fight for a better society, he used his several eminent platforms to push for change and encourage progressive ideas.

Banjo was full of grace, quiet dignity, deep understanding, wisdom, good humor, compassion, empathy, and humility. Every writer, journalist, teacher and student of English Language in Nigeria owes Banjo a debt of gratitude.

Maybe because of the several critically acclaimed books he authored, including Effective Use of English: A Developmental Language Course for Colleges and Universities (1976), Developmental English (1985), Making a virtue of necessity (1996), In the saddle (1997), The Wages of Obsessive Materialism (2008), The Deteriorating Use of English in Nigeria: 1st English Language Clinic Lecture Delivered at the University of Ibadan on Monday, 23 April, 2012, Humanity in Context (2016), Repositioning the Nigerian University System: Selected Speeches of Professor Emeritus Ayo Banjo in Commemoration of His 80th Birthday (2014) and Morning by Morning: The Autobiography of Ayo Banjo (2019).

Maybe because of his stratospheric rise from his native Oyo to the dizzying heights and success mountains. He was a former Vice Chancellor of University of Ibadan, visiting professor University of Cambridge and University of West Indies, President of the Nigerian Academy of Letters, Pro-Chancellor, universities of Port Harcourt, Ilorin and Ajayi Crowther, Fellow Nigeria Academy of Letters, Chairman, Sigma Foundation, Fellow of the Nigeria English Studies Association, Commander of the Order of Niger, winner Nigerian Nations Merit Award and chairman, of the Advisory Committee of the Nigeria Prize for Literature.

Or maybe because of his personal attributes: Banjo was a man with deep intellect, and compassion and a dignified presence. He did the right things and never sought the approval or validation of anyone or special interest. In addition, schooling in Lagos, Los Angeles, and Ibadan; teaching in Ibadan, Cambridge and West Indies and marriage across ethnic lines — Igbo and Itsekiri in-laws — gave him a cosmopolitan mindset.

However, a part of his legacy is personal for me, as I reflect on the work we did together promoting the literature and science prizes. And other projects. He was a great and useful ally. I couldn’t wish for a better mentor!

Our first contact was a telephone conversation facilitated by Professor Dan Izevbaye, then a lecturer with University of Ibadan. I had whispered to Izevbaye that I would like to meet Banjo to explore the possibility of inviting him as keynote speaker for the prize award ceremony.

Banjo’s voice, a deep baritone, cultivated, assured and friendly had floated down the speakers. And after pleasantries, he quizzed me about NLNG and the prizes. He was particularly interested in our vision and judging.

Banjo’s voice and polite conversation immediately puts one at ease. But I did not forget my manners; I was in the presence of a national treasure, if ever there was one.

I apologized for speaking to him over the phone; I had intended coming to meet him in Ibadan, if I had an appointment. He waived aside my effusive apologies.

Then I asked if he would consider being our keynote speaker. In our first year, we had Prof. Barth Nnaji and Prof. Wole Soyinka, I offered. Banjo who did not give me an answer said there were issues he would like to discuss with me, particularly the ban against foreign based writers. I listened carefully and then inquired if he would like to attend the next meeting of the Advisory Committee on Literature. We had pencilled him down for the keynote address, but we were sure he would add greater value serving on the committee.

A long pause. Then he reminded me that he had certain objections and we may perhaps not be comfortable with his views. I laughed and said “be our guest”.

The next day I sent him reading materials.

Like many Nigerians, Banjo had erroneously assumed that Nigeria LNG Limited introduced the ban (or exclusion clause) against foreign based Nigerian writers.

For a long time we resisted giving a direct response to the controversy raging in the press about issues regarding the prize. And I deliberately did not brief Banjo about them before the meeting.

Three issues stood out. One was the exclusion clause in the communique Siene Allwell-Brown and I signed with members Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA) and other members of the Advisory Committee for Literature Prize. The second was NLNG’s alleged high-handedness in replacing some writers on the Advisory Committee with new members. And the third was the no-winner verdict by the judges read at the 2004 award ceremony by Alhaji Abubakar Gimba.

We had erroneously believed that the controversies, lacking any merit, would go away. But they grew instead, because, as years passed, the arguments of unhappy former advisory committee members became more and more sophistic.

At the exploratory meeting on the prize, it was agreed that a four year cycle of prose, poetry, drama and children’s literature would give writers enough time to prepare for rich harvest.

The idea to ban foreign based writers came from ANA members in the committee. And It had a widespread support amongst the writers in the meeting. Another issue that got the enthusiastic support of the committee was the October 9th (or nearest Saturday) date for hosting the prize award ceremony yearly, proposed by Professor Femi Osofisan to commemorate the date of the first shipment of LNG from Nigeria.

We protested the ban, but considered it a lesser evil compared to their demand that members of the advisory committee could nominate judges and also compete for the prize.

It would, in our view, be incestuous, for anyone to play both roles. We had insisted that committee members interested in the competition should resign. No on should be allowed to appoint judges in his own case!

Before the appointment of the judges, members who wished to compete were asked to leave. The call for entries and judging process went smoothly — the long list, the short list and the final list containing the “winner, first and second runner up”.

On the night of final deliberation, I was invited by the judges. At the meeting, it was clear that something was amiss. The books on the final short list had too many errors – grammar, syntax, spelling and other flaws, they said. The least number of errors in each book was 60.

Some of the judges wanted to know if NLNG would permit that the authors on the final list to make corrections and republish so that their books would be error free. My response was that the revised books would be different from the ones entered for the competition.

I asked why the books could not be approved in their current state. The response was that they would reflect poorly on Nigeria literature if the prize winning books were riddled with grammatical errors. They judges would also be considered incompetent by their colleagues and general public.

Were the rest of the books not dropped for same reasons? I asked. Cleaning up the books meant that the judges simply aided one of the candidates to win. The public would be interested in the criteria for choosing the ultimate winner. And why others were not given similar privileges?

In the circumstance, they decided not to award the prize.

It was then a hostile review meeting that Banjo attended. In my welcome remarks I thanked everyone for their contributions and reminded them that NLNG had stoically borne the blame for their decision to exclude foreign based writers. I also requested that we expand the partnership to include other stakeholders.

There were various suggestions, including the Nigerian Academy of Letters. This was approved and Banjo, Izevbaye and Prof. Theo Vincent, who were members of the Academy of Letters were asked to consult with their colleagues.

Banjo argued unsuccessfully for the lifting of the ban on foreign based writers at that meeting and subsequent ones. He kept at it, for years without success and at some point NLNG unilaterally announced the lifting of the ban.

That was only the beginning.

A few years later, a judge colluded with a candidate and a former committee member and submitted an entry without declaring a conflict of interest. Because of the breach, we introduced a two-step judging process — Nigerian judges and an international subject matter expert, who will read the three books on the final short list and offer a verdict.

Banjo also played an active role in our efforts to set up a Gas Department in Rivers State University of Science and Technology, Port Harcourt in affiliation with Imperial College, London. It was a proposal eagerly supported by Dr. Chris Haynes, the Managing Director. After several failed efforts to engage the management of the school, we called on Banjo to broker a meeting.

Again, the Vice Chancellor was unavailable when we arrived his office for a pre-scheduled meeting. Attempts to get his attention was unsuccessful. We waited for hours!

When the VC’s staff learnt that Emeritus Professor Banjo came with the delegation and all hell broke loose. Suddenly, everyone was pleading for just five minutes for the VC to arrive.

As the meeting progressed we discovered that the university faculty was unhappy with a clause in our agreement with Imperial College London for exchange of faculty and grooming of staff of RSUST, who will in time, take over from the expatriates.

Many RSUST staff will be trained at Imperial College London as part of the program. RSUST staff were hostile to the idea of exchange of staff; they wanted to fill the slots immediately.

Deflated and incredulous, if Banjo felt the school’s management and faculty had committed some kind of offense against education or dishonored the citadel of learning, he did not show it.

He made no spectacle out of their choice to throw away such a golden opportunity. Advising the faculty on virtues of patience was the most ostentatious show of his disappointment.

There were more fights!

NLNG broke ranks with Academy of Letters because it wanted total control of the prize without the participation of interference other stakeholders. The request was not acceptable to NLNG.

Our position was informed by our experience with the science academy. Meetings of the judges of the science prize were always uninspiring and the outcome did not seem to serve national interest.

As administrators we took our case to Emeritus Professor Umaru Shehu, Chairman of the Science Committee and Banjo and they approved that since science is universal, the decision of the judges should be sent to a subject matter expert overseas for confirmation.

After that, no prize was awarded for science for over five years, because international scholar, after international scholar returned a “don’t-award” verdict. They did not see any merit in the recommended works!

The Academy of Science leadership was scandalized that its decision was constantly challenged. They complained that Nigerian scientists were no longer adequately recognised and asked for full control of the prize and judging process.

NLNG responded that the primary purpose of the prize was to recognise new ideas and original, actionable solutions that could help resolve national scientific and technological problems rather than to honour individuals.

We proposed a fundamental change in the idea behind the prize. In a nutshell, NLNG proposed that rather than honour individuals, the academy should identify and advertise national problems for scientists to provide solutions.

To ameliorate the situation, NLNG launched in 2014 a University Support Program as part of its commitment to develop education and complement government and stakeholders’ efforts.

NLNG spent about USD12 million (USD2 million per university) to build modern engineering laboratories and/or furnish them with cutting edge engineering equipment to aid teaching and research in six universities across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones.

The six universities and regions were University of Ibadan (South-West); University of Ilorin (North-Central); University of Port-Harcourt (South-South); University of Maiduguri (North-East); Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria (North-West); and University of Nigeria, Nsukka (South-East).

After parting ways with the Science Academy, ANA and Academy of Letters, the two prizes rested on Banjo and Shehu’s shoulders. NLNG in managing the prizes benefited from their considerable clout, wide contacts, integrity and prestige.

It was an assignment they took seriously. Banjo ensured that he read every book entered for the competition. He searched for the integrity of a story and was always on the lookout for a story that carried moral weight. But he never interfered with the judging process.

If there was a moment—a single incident — when the nation’s merit system was challenged, it came on the eve of the nation’s 50th Anniversary as NLNG prepared to honour 25 of Nigeria’s greatest scholars, artists and writers and 25 of her greatest scientists, some of them posthumously.

Again, Banjo was tapped to head the panel. The final selection was widely adjudged fair and just, a hard to comeby verdict in a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural and multi-religious country such as Nigeria. He binned all nominations in his name saying it was in appropriate to be both judge and competitor.

Whether or not our country gets better, a central question historians are sure to ask about Banjo’s era is why Nigeria lost its soul despite the presence and labours of giants like Banjo.

Many good men lost their souls and their way in Nigeria, but not Banjo. He held tight to what was most valuable about his work: his credibility as an arbiter of truth and broker of ideas. One hope’s historians and biographers will tell the story of this great man who never lost his footing. His autobiography, Morning by Morning, was a good beginning.

Mbanefo, former spokesperson of Nigeria NLNG, is the author of the widely acclaimed book, The Story of NLNG. He lives in Canada.